Go explore—on open tabs, lists and better representations for exploration

07 Dec 2021

#

A couple of years ago, a research paper from Uber AI came out and obliterated the previous algorithms on the Montezuma’s Revenge Atari game. Montezuma was one of the hardest Atari games to crack as it belongs to a class of games called “hard exploration problems”, where the agent has to “learn complex tasks with very infrequent or deceptive feedback”.

disclaimer: I’ve never played the game but i think the idea that made the algorithm do so well is simple and generally interesting.

Here’s the insight:

We hypothesize that a major weakness of current intrinsic motivation [adding an exploration bonus to actions] algorithms is detachment, wherein the algorithms forget about promising areas they have visited, meaning they do not return to them to see if they lead to new states.

By adding a component that keeps an archive of promising visited places, the algorithm was able to beat previous competitors by two orders of magnitude.

That made me think of open tabs on internet browsers. Open tabs is a recurring problem for people who engage in exploratory search. While they act like an archive of promising areas for future exploration, they mostly become a dump of articles never to be touched again.

That feeling when one finally closes a browser tab, after weeks of keeping it open in search of a moment to read it (which never arrived). Repeats 3 times: *The web is a river, don't try to hold on*. pic.twitter.com/dSjUYrVzMM

— samim (@samim) January 14, 2018

As we explore a new exciting domain of knowledge, we quickly become overwhelmed by the different possible avenues to explore (*opens new tab*). As one goes down one rabbit hole, we are quick to forget the multiple other avenues that had caught our interest early on. These different branches of exploration quickly lose their meaning, as we forget the context in which they were found, and so the tabs remain there until we reluctantly close them some months later.

This is how people kept multiple tabs open in 1700s pic.twitter.com/IfCraM1WW1

— Devi McCallion (@dei_genetrix) February 12, 2021

We know the tabs have value – why otherwise such pain in preciously keeping them open? but that value is gone when we go back to them, lost in the rapid stream pouring out of our information bottleneck.

If only we could keep those promising sparks we once saw, and re-visit them when the time is right!

My hunch is that much of it has to do with how we represent information, and one of my biggest grudges is our obsession with lists.

Here is a list of examples.

1) a list of tabs:

2) a list of songs:

3) a list of interesting people:

4) list of search results:

I could go on: movie lists, lists of recipes, bookmark lists, lists of youtube videos, lists of articles in a newsfeed…

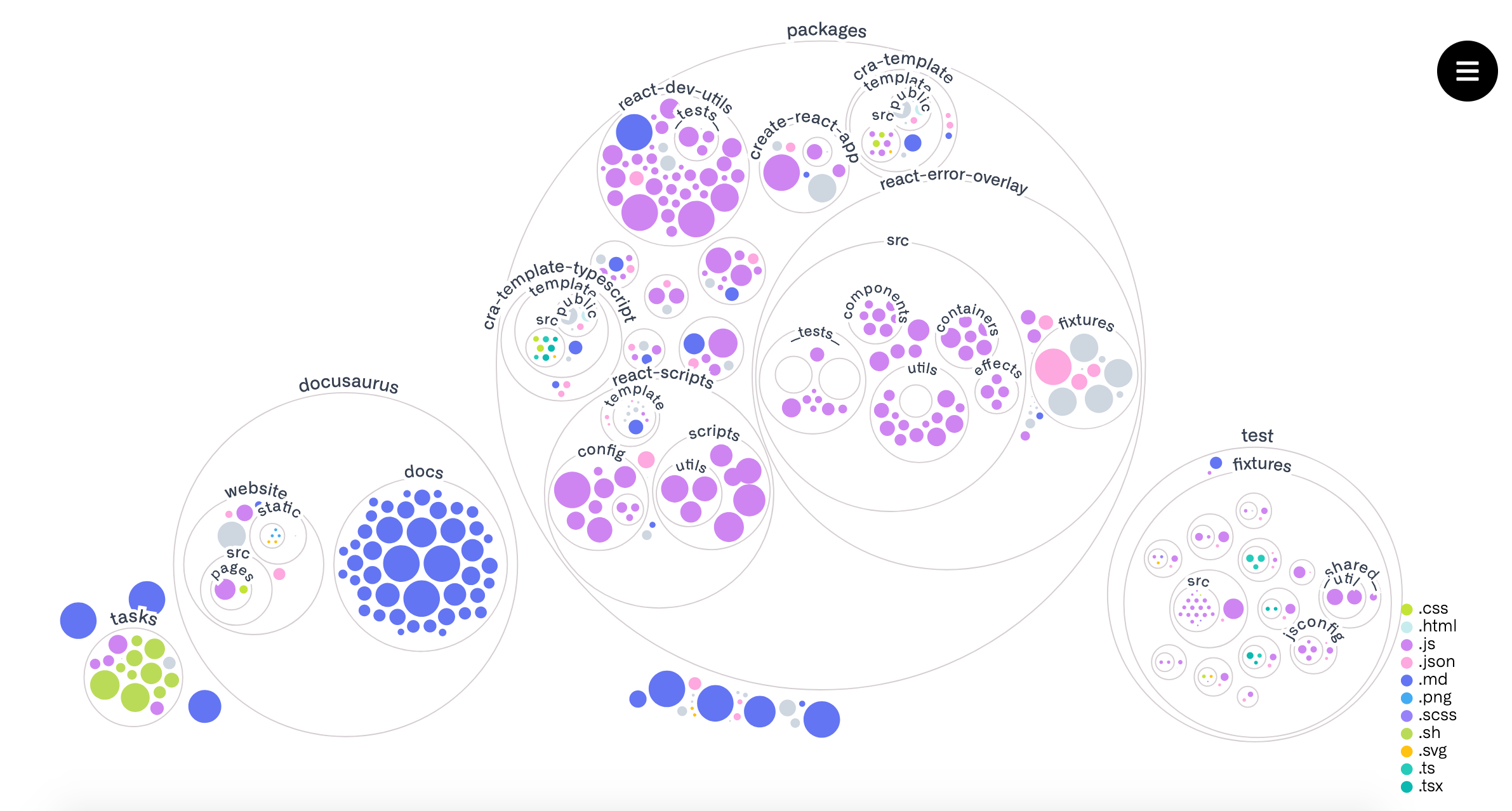

Lists are often great, but they’re terrible when exploring new or complex domains of knowledge, and they’re a very poor scaffolding for exploration. They’re the equivalent of a sad pile of papers, when what we need is maps. The documents could instead be spread out on the floor of a very large living room in thematic islands, or organised in enticing library alleys. In the examples above, items are interconnected in rich and varied ways–capturing these connections is what can support learning and discovery.

Evidently, many people have spent a lot of time thinking about these things, and for a long time, like Vannevar Bush’s memex, or Ted Nelson’s Xanadu. I touched upon this a bit in a previous blog post on annotations and linked notes.

Some related interesting projects I’ve bumped into include:

- Every Noise At Once tries to map music genres

- fingerprint provides visual explosions of github repositories

- Tree style tab keeps tabs as trees – where newly opened tabs are “children” of the tab they originate from. (This is a relatively modest example, but shows that a simple effect can go a long way)

)

There are efforts in mapping communities, organisations, research domains etc, and this is easier than ever with tools like word embeddings or topic models.

Maps empower active search processes, providing people with a greater sense of direction. It’s also about time we move on from repeated queries in a search box and doom scrolls.

Who knows, perhaps better interfaces and intuitive representations could lead to improvements in exploration orders of magnitude greater than what we have today?