Minimising WTFs in fencing bouts - a pre-olympic ramble

25 Apr 2021

Using simulations to reduce the number of upsets in fencing and make it a more exciting spectator sport

After a year without international events, I watched the fencing European zonal qualifier for the Tokyo Olympics with excitement.

As it is custom in fencing, I watched a match run away from a fencer who was clearly better, more experienced than their opponent. They were probably more than 300 spots ahead in the world ranking and had fenced very well in the previous bouts. So what happened?

A recap for the novice, fencing consists of 3 different weapons: foil, epee and sabre.

Epee seems to get a lot more upsets like this than the other two weapons, and when looking at stats it looks a lot harder to get consistently good results for the top athletes. When comparing the top 16 in foil and epee, foilists generally collect more world ranking points than epeeists. This means that throughout a season, they perform well at most competitions.

Seeing the same people perform well leads to more attachment. It also creates narratives and rivalry. This is what brings enthusiasm to a spectator sport.

My goal here is to use numbers to show why reformatting fencing matches makes sense, and would reduce the number of upsets and make fencing more enjoyable as a spectator sport.

The format of a fencing match

A fencing competition consists of a sequence of bouts to 15 (3x3 minutes). There are 64 fencers in the final draw, which happens on a single day, with 6 direct elimination bouts to win the tournament. In this part, I'll use model simulations to evaluate how different formats could reduce the number of upsets. Race Imboden, foilist, 3x Olympian and fencing superstar (if such thing exists) discussed similar ideas on his old blog.

The Idea is to install a best 2-out-of 3, or 3-out-of-5 (15 touch) bouting system. The idea would be to enhance three aspects of the sport; the athleticism of the competitors, emphasize consistency of results, and increase Spectator enjoyment.

As any fencer knows, 15 touch bouts are very short in the grand scheme of things – many times these bouts can complete before the first period has expired. In this time period – even simple mistakes can lead to a devastating end.

How many times have we seen upsets of a physically, technically, and more consistent athletes by unorthodox lesser athletes?

Simple modelling framework

We’ll model upsets by using probabilities to simulate possible outcomes. If two fencers have the same skill, we can assume that who gets the hit is the same as flipping a coin. The first to get 15 (Heads or Tails) wins the match.

If a fencer is more skilled, it’s similar to having a biased coin. So if a fencer is better, you might say it’s like flipping a coin that has 55% probability of H and 45% probability of falling on T.

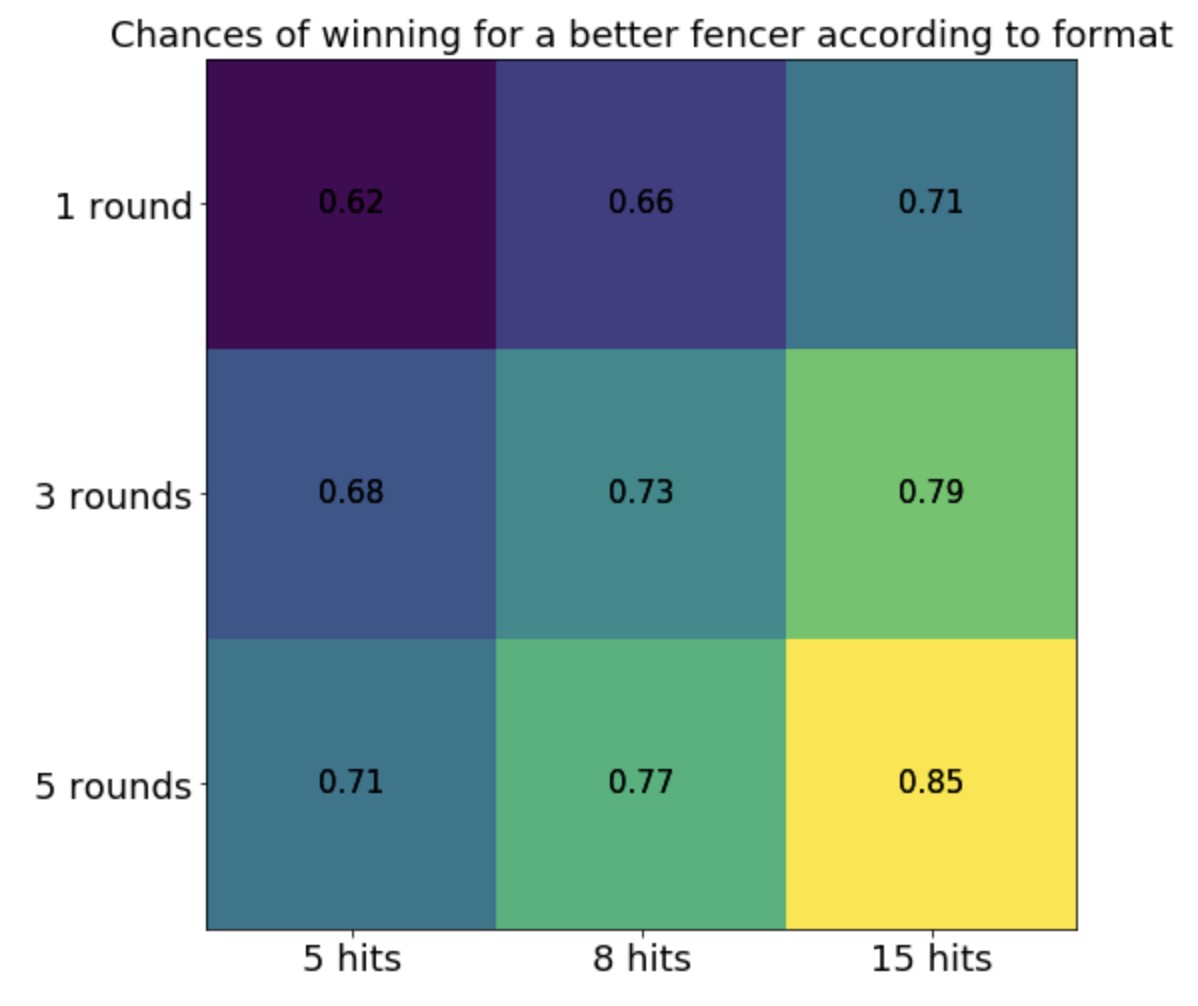

If the match was a single hit, then the better fencer would have 55% percent chances of winning. Now for a match to 15 hits (we simulate this 10,000 times), the superior fencer ends up winning 71% of the time. For best of 3 matches to 15, the superior fencer ends up winning 79% of the time.

In the figure below, we run simulations for matches of different lengths (5 hits, 8 hits, 15 hits) and with different legs (single bout, best of 3, best of 5).

A bit about Epee and why it’s so damn hard

One of the main differences between the weapons in fencing is their rules. Sabre and foil both have what’s called the “right of way”, which means that only a single fencer can be awarded a hit at a time. It’s up to the referee to decide who that is, if both fencers hit their opponent at the same time. This is done based on who had the initiative, e.g. starting the attack, taking the last parry etc. This is kind of like having the ball in football. To score, you need to have the ball. If your opponent doesn’t have the ball, they can’t score, and to score they need to steal the ball first. That’s also why we talk about fencing “phrases”, as the exchanges between fencers become almost conversation-like.

In epee, the ref doesn’t have as much of a say. Fencers can hit each other simultaneously and one point is awarded to each. That’s basically as if each football team had their own ball. This can give you a hint as to why random stuff is more likely to happen in epee.

The lack of right of way makes it a lot more difficult to control your opponent in epee. This is maybe exagerated by the fact that the whole body is the target, which adds an additional layer of complexity. You don’t only have to protect your torso, there’s also the feet, the hands, the head etc. This is one of the things that make epee so fascinating, as the athletes have to constantly be aware of every movement of their opponents, and cautiously adjust the level of risks they are taking. In sabre and foil you are either attacking of defending. In epee it’s not so clear cut.

There’s also a significant advantage from being in the lead in epee. Once you are a couple of hits ahead, you can strategically minimise the amount of risk you take and let the opponent take the initiative. Because they have to take all the risk, they end up being in a much more vulnerable position. This also has a parallel with football, where once you’ve scored an early goal you might choose to put all your players in defense.

You can maybe imagine that in epee, if you are slightly less skilled than your opponent but manage to get an early lead, you might hang on to that advantage and still have a good shot at winning the thing.

Lead dynamics in epee

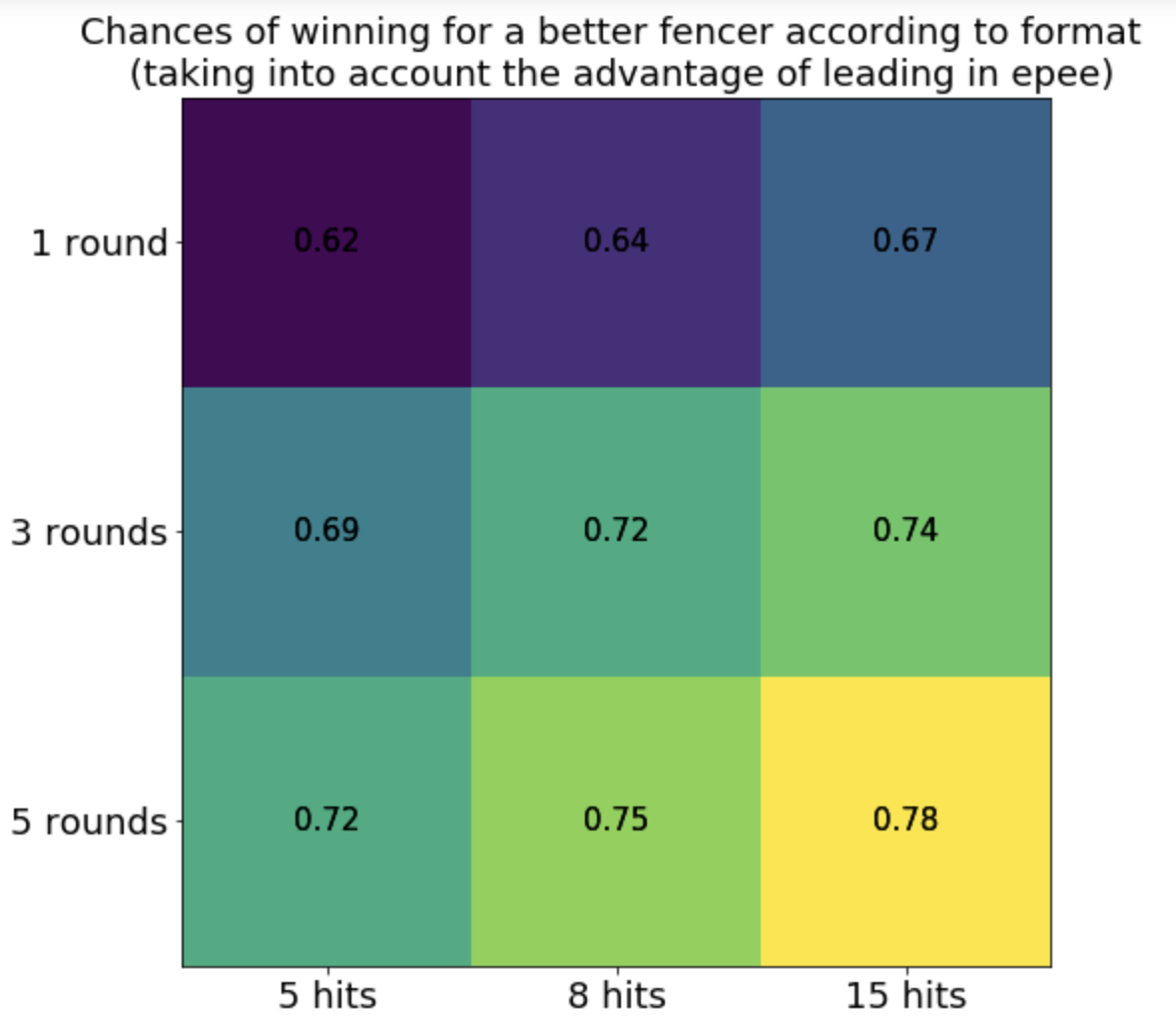

Let’s now add in the dynamics of the advantage of being in the lead in epee to our modelling exercise. I define it here by saying that if a fencer is two or more hits ahead, they get a higher probability of winning a hit (e.g. 57.5% instead of 55%).

For a single match to 15, the chances of winning for the underdog jump from 29% to 33%, which is quite significant.

If instead, matches were to 8, and the winner was decided by the best out of 3, this would go down do 28%. Perhaps surpisingly, if increasing this to best of 3 matches to 15 points, the underdog probability of winning only decreases by 2% (26%).

Making it to the best out of 5 matches (i.e. first to three wins) to 8 hits reduces this chance down to 25%. What comes out quite clearlly is that increasing the number of hits in epee does not increase the odds of the better fencer by much, but having more legs does.

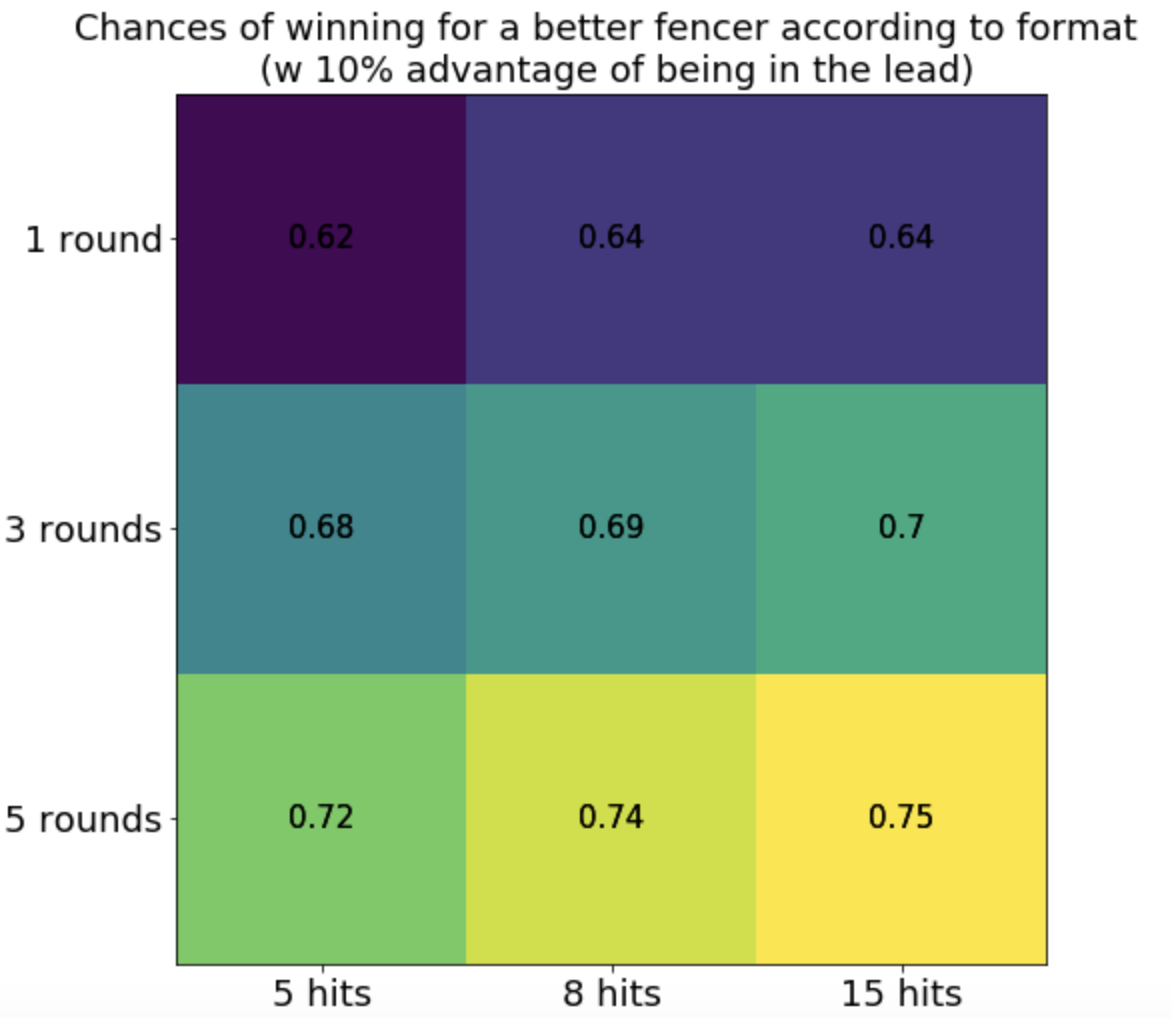

Let’s look at the numbers for an even stronger lead advantage (10%)..

Here it becomes even clearer that more legs is the only way to make match outcomes more reliable.

Arguably, separating the scoring would also add excitement to the match. I doubt anyone would be able to watch a 5h long match of tennis if they hadn’t come up with a clever way of splitting the match in smaller sections that create series of minis drama throughout the match.